Spring 2002

Comics as a Storytelling Medium:

Using Comics in the Design Process

Jason Moore

IT Product Design

MCI Institute for Product Design

University of Southern Denmark, Sønderborg

jmoore@sober.dk

User-centred design requires that designers attempt to understand the values, attitude and motivations of the people who will use the eventual designed artifacts. This paper suggests that collecting stories from these people is an effective way for a designer to gain the required understanding. More specifically, simple drawings can be used to elicit these stories. Two techniques are presented: a card game where the a series of cards are sorted, and an exercise where a story is created from comic elements. Benefits and limitations to these techniques are also described.

Keywords

participatory design, storytelling, stories, drawing, comics, cartoons, games

INTRODUCTION

User-centred design requires designers to know about the people they are designing for and their environment. The role the designer must play to acquire this knowledge ranges from the observational ethnographic approach of "hang around, talk to folks, and try to get sense of what is going on" [1], to quantitative surveys. The drawback to the ethnographic approach is that it requires waiting an unknown amount of time for something interesting to "happen", and what does happen may not be relevant to the designer's area of inquiry. Surveys achieve focus but at the cost of limiting the scope of the responses to stay within the designer's assumptions. The designer can only hope to gain a better understanding of concepts they have defined; no new concepts will be generated. A middle ground would seem to be qualitative questions that allow for people to better express themselves and introduce new concepts, but the risk is that with open ended questions that don't offer a structure people will "freeze up" as they are unsure of what they are expected to say. The challenge is to engage the people that you are designing for with a topic, but not force them to think along a certain line of thought. Stories are ideally suited for this challenge.

THE VALUE OF STORIES

Stories are valuable to the designer for their literal content, which helps to educate the designer about the details of an unfamiliar environment. Another important aspect of stories is that they reveal how the storyteller sees the world. Erikson [2] notes that stories "provide the designer with a glimpse of what the user's terrain feels like". Developing an understanding of this subjective experience is a crucial factor for design success as products become more complex [6].

The problem remains of how to actually get stories from people relating to a particular topic. Fortunately, storytelling has the following quality: it becomes easier to tell a story when a structure is provided than when no structure is given. For example, if I were to ask you to, "Tell me a story.", you would probably freeze trying to think of something to say. If I instead ask you to, "Tell me a story about a fish, a glass of water and a camel" it is almost impossible to not immediately create an image and a simple story to go along with that image. It is also important to note while your story contains those three elements, it is still more your story than it is mine.

The next section will discuss how comics are an excellent tool to add this required structure to inspire storytelling.

![]()

CARTOONS AND COMICS

A simple cartoon drawing can have many interpretations. Consider figure 1. Is it a picture of a coffee break, breakfast at home, an employee review, or something else? There is no correct answer: it could be anything. But, it isn't. What you choose to see is based on your personal experiences. S. McCloud in "Understanding Comics" writes, "When you look at a photo or realistic drawing of a face you see it as another. But when you enter the world of the cartoon you see yourself" [4 Pg. 36]. When you look at a cartoon, you see your world, not someone else's. This personal interpretation makes comics an ideal medium for a designer to access people's subjective experiences.

![]()

When you have more than one cartoon image, you move into the realm of the comic and storytelling. Consider figure 2. What happened in this comic? Why did one person leave? Similar to a cartoon drawing there are many possible interpretations. But, a new dimension has been added. Not only is each cartoon image is open to interpretation, but a new interpretation has been added by the viewer to explain what happened between the two frames. This is another way that comics tap into peoples experiences. S. McCloud writes, "Between these panels, none of our senses are required at all. Which is why all of our senses are engaged". [4 Pg. 89] This ability of comics to leverage these two levels of interpretation, first with the images and second with the sequence is the basis of the following two techniques.

CARD SORTING

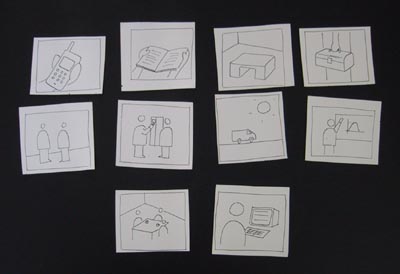

The card sorting technique uses a series of cards, each printed with a simple cartoon drawing. The cards are spread out on a table and the participant is asked to sort the cards based on a criteria.

The cards in figure 3 were created for a project to envision how a manual for a frequency converter (an industrial motor control) might look in 5-10 years. We were interested in the relationship (if any) of the manual to learning about how to use the frequency converter. We asked our participants to, "Sort the cards based on how important you think they are for learning how to use the frequency converter." The participants typically spent 20-30 seconds moving the cards around on the table as they worked out an order. Sometimes our participants would stop to ask what a particular image meant. Since our interpretation was irrelevant we replied, "Whatever you want." If a participant was obviously unsure about what to do with a specific card we suggested that they didn't have to use all the cards.

![]()

After the cards were sorted, the participants were asked to explain the order. Typically this involved the participant pointing at each card in the sequence and relating it to their experience. For example, while pointing to the card with an image of a cell phone a participant told us, "If I need help setting it up, I call the man who sold it to me." The order of the explanation always moved from the most to least important.

Once the order of the cards was explained, it was possible to go back into the story and get more detailed information by pointing to a particular image and asking follow-up questions.

There are three main benefits to this exercise. The first is that while the designer has to rely on their assumptions while choosing what drawings to include on the cards, the simplistic nature of the drawings allows for surprises and alternate interpretations. The designer is not forcing the participant to think in a certain way, but is instead providing inspiration.

The second benefit is that by ordering the cards, the participant has structured the cards according to their personal experience. As a result they can explain the sequence of the cards without having to be prompted by questions - the designer only has to watch and listen. After the explanation, the visual nature of the structure allows the designer to jump to any part of the story, by pointing to the card and asking a more detailed question.

A third benefit is that the cards become the focus of attention which takes some of the pressure off the participant so that they can relax and speak more freely. For this reason, card sorting is an excellent warm-up activity.

COMIC CULTURAL PROBE

A more elaborate comic storytelling technique is in the tradition of "cultural probes" [3], where participants are given exercises to work on by themselves in their own environment. Gaver and others [5] have used a wide variety of tools such as collage, postcards and disposable cameras to involve their participants and encourage responses. The comic technique outlined here is another tool in the cultural probe creator's tool-box.

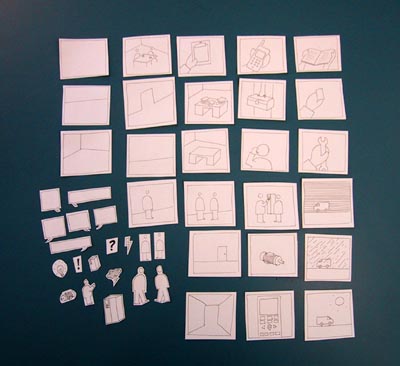

The comic cultural probe was also for the same project as the card sorting exercise. Another area of interest was how manuals were used for problem solving. We created various comic elements, such as panels, empty speech balloons, and cut out drawings of people, motors, and frequency converters. (See Figure 4) Each piece contained a sticker with backing so that it could be easily glued to a piece of paper. The instructions (Figure 6), drawn in the same style as the comic elements, asked the participants to use the comic elements to tell about the last time there was a problem with the frequency converter. The culture probe was left with our participants after our first meeting, and picked up about a week later.

![]()

When the probes came back, they were very obviously a rich source of information, but we had difficulties analysing them. The open interpretation of comics which allowed our participants to relate and connect with these images to their own experiences, similarly meant that it was difficult for us to understand the comics without adding our own experiences and biases. It was essential for us to bring the comics back to our second interview so that our participants could use the comic to tell us the story in their own words.

After hearing the participants walk through their comics, it was clear that the participants interpreted the suggested topic differently than we did. For example, we thought "problem solving" would mean fixing a breakdown, but one of the participants (Figure 6) interpreted this to mean, "how to build something new". He told a story of how he setup two frequency converters to work together. Another participant saw his whole job as "problem solving" and so he told us a much larger story about "how he uses the frequency converter"; from talking to his customers, to designing the system, to ordering and installing the frequency converter, and finally to the topic we suggested of fixing a problem for a customer. The participants re-framing of the suggested to topic to what they want to talk about indicates that this technique is better suited to the early stages of the design process where design opportunities have not been formulated. The comic technique is not a tool to to inquire into specific predefined problems.

However, the comic does allow for a more detailed discussion about the elements and framework defined in the story. For example, the story in Figure 5 refers to a "Magflow" which is a component that measures the amount of liquid running in a pipe. This was our second visit to our participant's workplace, but flow meters had not been mentioned before. We asked more questions about them and soon the problem outlined in the story took on new meaning: even though both the flow meter and the frequency converter were made by the same company, the product manuals were not adequate for getting them to work together. Our participant had to call the company's support desk to get the required information. This realization led to a series of concepts concerning expanding the scope of the manual from a specific product to include systems and applications. Our participant's comic played a key role in helping us to re-frame our inquiry.

SUMMARY

This paper has described two techniques to use comics to help the designer better understand the world of the people they are designing for. A single cartoon image holds many possible subjective meanings. The interpretation and arrangement of these images allows for participants to tell stories in "real-time" during an interview with the designer or while working in private while the designer is not present. These stories communicate the values, and experiences of the storyteller and which can serve as a starting point for a more detailed inquiry. The role of the designer is to listen to these stories and then focus in on anything surprising.

FUTURE WORK

Both of the comic techniques outlined in this paper have focused on capturing stories from past and current experience. The author is also interested in seeing how effective comics are at helping participants express possible future experiences, or how things could be. The potential benefit is that techniques using comics could bring participants closer into the idea generation and selection part of the design process. In other words, comics could bring participants into the designers world the same way that they can bring designers into the world of the participants.

REFERENCES

[1] Wolcott, Harry F., "The Art of Fieldwork", AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek (1995).

[2] Erickson T., "Design as Storytelling", interactions, p. 30-25, ACM Press, New York (July/August 1996).

[3] Gaver, B., Dunne, T., Pacenti, E., "Design: Cultural Probes", interactions, ACM Press, New York (January/February 1999).

[4] S. McCloud, "Understanding Comics", Tundra Press, Northhampton, (1993).

[5] Gage, M., Kolari, P., "Making Emotional Connections Through Participatory Design",

(March 2002).

http://www.boxesandarrows.com/archives/print/002322.php

[6] Buchenau, M., Suri, J. F., "Experience Prototyping", Conference Proceedings on Designing

Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods and Techniques, p. 424-433, ACM Press, New York (2000).

Have a suggestion about this page? Send a quick comment:

iphone apps

![Pronounced [Zin-site] Xinsight logo](/images/xinsight_reveal_dark.gif)